The answer, strictly speaking, is - not a lot.

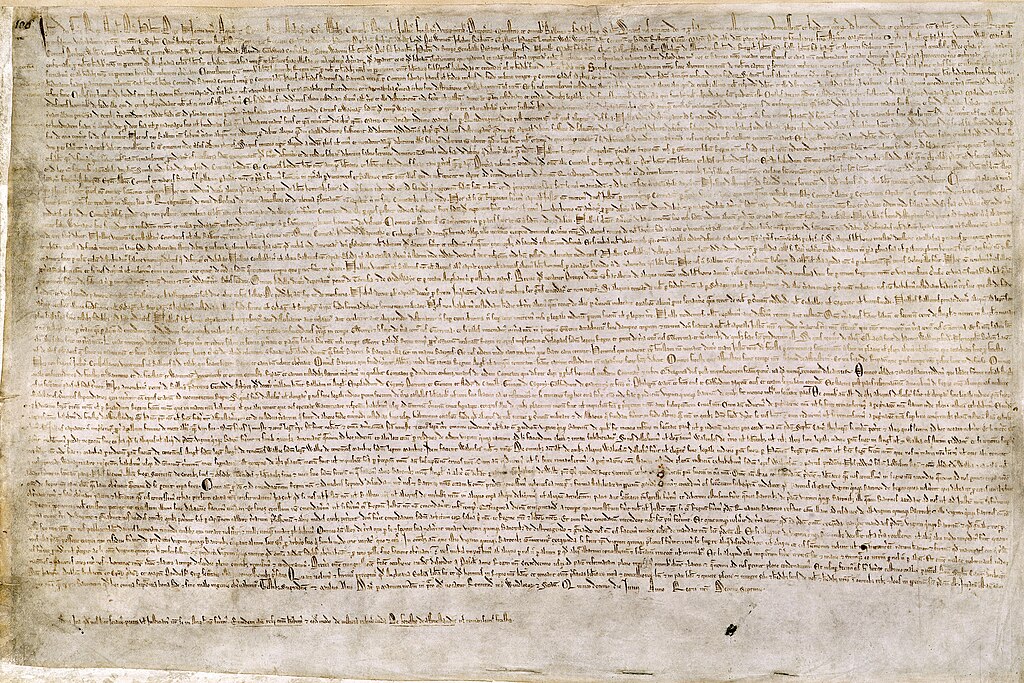

Back in the early summer of 1215, England was ravaged by civil war. On one side, a group of rebel barons and their mini-armies, and on the other King John, supported by another set of noblemen. The rebels were getting the upper hand, so to play for time the king negotiated a deal with them. The result was Magna Carta, or the Great Charter.

Later generations have often regarded it as a constitution that gave us fundamental rights such as universal civil liberty and democracy. But the truth is that it did no such thing.

Most of the document is peppered with feudal jargon - ‘amercement’, ‘trithings’, ‘halberget’ - hardly words to echo down the ages. And anyone looking for some universal, everlasting statement of principle, such as ‘No-one is above the law’, is in for a disappointment. Even when we do stumble on a few lines to make our hearts leap, historians step in and pour cold water on our enthusiasm. Take its most famous words:

‘No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions ……. except by the law of the land.’

Stirring stuff. But note, this wonderful right applied only to ‘free men.’ In 1215, this was a small, privileged group of around one in four of the male population. Most of the rest were serfs, that is near-slaves, tied to serving their local lord. And you’ll notice that it’s freemen not women. The law at this time hardly recognised the existence of this half of the population. It’s upper class men looking after themselves.

So, did Magna Carta do nothing to protect what we would call the ‘human rights’ of ordinary English folk? Well, it did decree that royal judges should not fine an unfree peasant so heavily that he lose all his crops and farm tools. A humane act? I'm afraid not. The barons, whose rebellion Magna Carta was designed to buy off, were worried that the king would strip their serfs bare before the barons themselves could milk them dry.

But that’s not the whole story. We shouldn’t run away with the idea that Magna Carta is somehow a fraud. There are two powerful reasons why this year we’re rightly celebrating the original 1215 Magna Carta.

The first is because it showed that even a king must obey the law. The Great Charter doesn’t spell this out in so many words. But many of its clauses are examples of how those who govern us are subject to the law just as much as to the rest of us.

And secondly, although its most famous clause applied only to a privileged minority of men only, it did establish an important principle: that arbitrary punishment without trial is wrong. It was a foundation that could be built on. A hundred and thirty-nine years later, in 1354, Magna Carta was re-written and re-issued. It now stated that 'no man, of whatever estate or condition he may be’ could be punished without 'due process of law.' And if we recognise that the status of women in fourteenth century society made it unthinkable for them yet to be included, we have a fundamental right on its way to being universal.

So Magna Carta developed and grew over the centuries to become a beacon of justice and freedom from oppression. It helped bring down a king in the great clash between crown and parliament in the seventeenth century. It was cited in the American Bill of Rights. The nineteenth century Chartists battled in its name for a radical reform of England’s political system. It inspired the constitutions of Australia, Canada and India. And today, when someone demands ‘due process’ to complain about some injustice – be it ever so minor - they’re quoting from Magna Carta.

Not bad for the manifesto of a few thirteenth century noblemen. We ordinary folk have made it our own.

Derek J. Taylor is the author of Magna Carta in 20 places. For over 800 years, Magna Carta has inspired those prepared to face torture, imprisonment and even death in the fight against tyranny. But the belief that the Great Charter gave us such freedoms as democracy, trial by jury and equality beneath the law has its roots in myth. Back in 1215, when King John was forced to issue Magna Carta, it was regarded as little more than a stalling tactic in the bloody conflict between monarch and barons. Here, Derek Taylor embarks on a mission to uncover the ‘golden thread of truth’ that runs through the story of the Great Charter. On a journey through space and time, he takes us from the palaces and villages of medieval England, through the castles and towns of France and the Middle East, to the United States of the twenty-first century. Along the way, the characters who gave birth to the Charter, and those who later fought in its name, are brought to life at the places where they lived, struggled and died. As he discovers, the real history of Magna Carta is far more engaging, exciting and surprising than any simple fairy tale of good defeating evil.