![File:Richard III earliest surviving portrait.jpg]()

Scrape away the accumulated filth of tainted evidence which has disfigured the memory of Richard III for the past five hundred years, and there is really very little that remains mysterious about the outlines of his story. In fact it can be summed up in one sentence: he accepted his dead brother’s throne when it was offered him at a moment of desperate crisis, and no record survives of the ultimate fate of his nephews.

From these flimsy foundations has grown the grotesque figure of evil which was the work of Henry Tudor and his propagandists. Therefore, in considering the evidence either for or against Richard it is essential to trace it to its source, and in assessing its value, to take into consideration the background, personal prejudices and ulterior motives of the-witnesses. Thus the evidence of John Rous, whether in Richard’s favour or not, is of little value, for the man was obviously a time-server whose aim was to please the king of the moment, whether Edward, Richard or Henry.

Mancini, as he himself admitted, retailed the current gossip as he heard it, giving a vivid picture of the difficulties with which Richard had to contend. The writer of the Croyland Chronicle evidently disliked Richard even when he was Duke of Gloucester and disapproved of his accession, regarding it as a usurpation. Many worthy people at the time, not knowing the urgent necessity to keep the peace which lay behind Richard’s acceptance of the crown, undoubtedly thought the same, and Richard himself was under no delusion as to the censure which his action would incur in many minds. None the less the chronicler tries to be fair, though his information is by no means always accurate.

Writers who lived during Richard’s lifetime but who wrote after his death, such as Fabyan and the writer of the Great Chronicle of London in England, and de Commines in France were either, as in the first case, pro-Lancastrian, or, as in the second, anti-English, and were further influenced by the Tudor line, which had become the official and generally accepted version within a few years of Bosworth. They were thus prejudiced and their evidence is correspondingly suspect. Later writers, such as Polydore Vergil and More, depend entirely on hearsay; in the case of Vergil the inspiration comes from Henry VII and in that of More from Morton, which practically rules them out of court. In every case ‘common fame’, in other words vulgar gossip, is the source quoted.

It will therefore be seen that the contemporary or near contemporary chroniclers are of little value, and the only reliable sources of information are the records of the period, both public and private, of which a considerable number have survived, contrary to the generally accepted view. Among these are the record of Richard’s legislation in the Parliament Rolls, references to him in municipal records, his grants in the Patent Rolls, and various miscellaneous documents relating to his household and his public departments. There are also a few revealing private letters which still survive and show a very different man to the monster of legend. Among the latter is a letter to his mother (BL. Harl. MS. 433) which goes far to prove that mother and son were very close to each other and to dispose of the story that Richard caused Shaw to slander the Duchess of York in his sermon at St Paul’s Cross. In the same collection there is a letter to his Chancellor, the Bishop of Lincoln, written when his Solicitor General, Thomas Lynom, succumbed to the charms of the fair Jane Shore and wished to marry her, in spite of her complicity in the Hastings-Woodville plot and her subsequent disgrace.

The letter is a model of tolerance and kindliness; far from forbidding the unwelcome match and ordering the disgrace of Lynom as he might well have done, the King merely asks the bishop to use his influence to stop it, adding that if Lynom is resolved he will give his consent, and in the meantime Jane is to be released and placed in the care of her father. Hardly the attitude of a tyrant.

There is also the letter now in the Public Record Office, written to the Chancellor at the time of Buckingham’s rebellion, with a postscript in the King’s own hand expressing his horror at his friend’s treason and calling Buckingham ‘the most untrue creature living’, which he undoubtedly was. There is no trace of the cruel monster in any of these letters; indeed they arc those of a gentle and honourable man and tell us more of the real Richard than anything else could possibly do. They are not official documents written with one eye on public opinion and the other on posterity. His legislation shows consideration for his poorer subjects and a zeal for justice which benefitted the people while it lost the King powerful support. The civic records of York show the esteem and affection in which he was held by that city when he was Duke of Gloucester, and the touching entry in the council minutes recording his death is as fine an epitaph as any man could wish for:

‘King Richard late mercifully reigning over us was through great treason … piteously slain and murdered, to the great heaviness of this city.’ Brutal tyrants arc not so mourned. The homely fact that he was known as ‘Dickon’ to his meanest subjects is in his favour, for men who are hated arc not called by affectionate diminutives. His loyalty to his brother was remarkable in that time of easy treasons. The only recorded occasion on which he opposed Edward was at the Treaty of Picquigny, when he alone refused the bribes of the King of France and spoke against what he considered to be a shameful betrayal of his country’s interests and honour.

Far from being the subtle schemer and ‘deep dissembler’ which later chroniclers accuse him of being, he had a great distaste for intrigue. He kept himself apart from the constant plottings which riddled Edward’s court, going about his business in the north. Indeed, so little was he versed in intrigue that when he met it himself he was quite incapable of dealing with it. His own nature put him at a hopeless disadvantage with men like Buckingham, Hastings, and Stanley, to whom the atmosphere of plot and counterplot was as natural as the air they breathed. They were incomprehensible to Richard as he was to them; each judged the other by his own standards until it was too late and tragedy was upon them all.

It is impossible for the most biassed anti-Ricardian to find any tenable charge that can be brought against Richard up to the time of Edward’s death. He was a loyal and honourable man to whom his brother need feel no hesitation in committing the safety of his wife and children and the welfare of his country. Had that been all that Edward bequeathed to Richard the sequel would have been very different, but he was also leaving to his younger brother an impossible situation. From that unspoken bequest arose all the disasters of the next two years, culminating in Richard’s own betrayal and death and the end of the House of York.

It is important to judge Richard’s actions after Edward’s death as we find them recorded at the time and without the embellishments of later writers, who, though they like to assume an inside knowledge of his motives, are in no position to tell us what went on in his mind.

Richard’s actions on receiving the news of Edward’s death away in the north were irreproachable. The ride to York with his train of mourners, the requiem mass and the public oath of allegiance to his nephew were both natural and fitting. There is no sign of indecent haste or impatience to ride south at speed and seize the reins of power. Even after receiving Hastings’ news of what was going on in London he does not summon reinforcements but continues on his way with his small escort to meet his nephew at Northampton, and it is only here, after receiving further alarming news, that he takes the first strong measure to deal with the crisis brought about by the Woodvilles.

It is from now on that it becomes possible to put two diametrically opposed constructions on Richard’s actions, the one honourable and the other base. The Tudor historians for their own reasons have chosen the latter; all Richard’s acts arc diabolical, his motives the very worst. In order to make their version at all consistent they have juggled with facts and dates, and where these have proved intractable they have not scrupled to fall back on sheer invention. On the other hand Richard is entitled to be judged, in default of direct evidence, in the light of his own past record- the record of a man who for thirty years had shown himself loyal, honest and trustworthy. It is unlikely that such a man should almost overnight become false, double-dealing and perfidious. Evidence of character is all in Richard’s favour and in its light the events of that summer of 1483 are at least comprehensible, whereas the Tudor version makes them improbable beyond the wildest imaginings.

Every act of Richard’s till the middle of June is entirely consistent with an intention to crown his nephew. Not only is the boy treated with every respect as King and the preparations for his coronation speedily carried on, but the fact that Richard made no attempt to send for reinforcements seems conclusive proof that he was not contemplating any drastic change of the accepted plans. The shattering upheavals that took place between June 9th and 25th clearly indicate a crisis as unexpected as it was serious, and the urgent call to York for help on the 10th is not the action of a man who has been carefully plotting a coup d’etat in his own favour, but rather of one who is suddenly confronted with a desperate and unexpected emergency. The whole incident of Shaw’s clumsy sermon which was much more calculated to alarm the people than to allay their fears has an atmosphere of panic about it which is very foreign to Richard’s character but may well have reflected the feeling of the Council, faced with the problem of an illegitimate heir, Woodville plots, an uneasy country, and the threat of civil disturbances. It is not surprising if the citizens, frightened and bewildered by these sudden changes which they did not understand, were at first reluctant to commit themselves and became the prey of inspired rumour. Who should blame them? It was only when Richard had finally accepted the crown and had taken his seat on the King’s Bench in Westminster Hall that the common people felt it safe to acclaim him, but when it came, their approbation was whole-hearted, and throughout the coronation celebrations there is no hint of there having been unrest or dissatisfaction.

Richard’s real motives in accepting the crown remain buried in his own heart, as he has left no personal record which could supply a clue to his thoughts. They were probably, as is usually the case, mixed, but it is certain that he capitulated to the urgent demands of the leading men of the country, and it is equally certain that by so doing he saved it from a renewed outbreak of civil war. He was no more a usurper than his brother Edward had been, and neither then nor at any later time had he cause to fear that his title, confirmed by the Titulus Regius, could with reason or legality be called in question. He had therefore no reason to wish his nephews dead. On the contrary, their continued existence was a safeguard against an attempt on the throne by Henry Tudor, the only potential pretender, through marriage with the boys’ sister.

It is significant that the only public reference to their supposed murder comes from the Continent, when, in January of1483/4 the French Chancellor, in a speech to the Etats-Generaux, accuses Richard of having had them put to death. His inspiration probably came from Mancini’s gossip, for Mancini was a friend of the Chancellor. Morton had also arrived in France shortly before. The Great Chronicle of London records that after Easter 1484 there was ‘much whispering among the people that the King had put the children of Edward IV to death’. Thus it will be seen that the stories were current in France sometime before they were at all general in England, and it is not difficult to trace their source to Henry Tudor and his advisers.

Rastell in his Pastyme of Peoples tells of a variety of stories which went the rounds as to the fate of the boys, thus proving that nothing was known and that the various stories were nothing but tittle tattle. The secrecy in which the whole affair was wrapped is in itself proof that Richard was not their murderer. If for any reason he had decided that their deaths were necessary he would have had to give out some explanation of their fate, for obviously a secret murder would defeat its own ends. If it was expedient that they should die, it was equally expedient that they should be known beyond all shadow of doubt to be dead.

Richard’s only course would have been to let them be seen to be well treated until speculation as to their future had died down, then arrange a murder which would look like a natural death – not a difficult task in those days of epidemics and little medical knowledge – followed by an exposure of the bodies at St Paul’s and a funeral befitting their father’s sons. Richard could have picked his own time for the murder and if he had been what the Tudors made him out to be, cruel, deceitful, a ‘deep dissimular’, this is what he would have done. The one thing he could not afford was a secret crime, followed by a mystery, at a time when there had been considerable speculation as to the future fate of the children, and at the beginning of what there was every reason to suppose would be a long reign.

It is impossible to say with certainty that any person is incapable of murder. In the history of crime the most unlikely people have committed the most improbable homicides. Given a sufficient motive, enough courage, and the opportunity, we are all potential murderers; but if ever there was a man of whom it could be said, having regard to the circumstances and all the reliable evidence we have as to his personal record and character, ‘this man is incapable of this crime’, then that man is Richard III, and the crime is the quite pointless and incredibly stupid murder of his nephews. There is no single factor which could account for his guilt; no motive, nothing in his previous character or in his subsequent treatment of others. Yet it is not any of these things which speak loudest in his favour, nor even the implied testimony of Elizabeth Woodville’s confidence in him six months after he was supposed to have murdered her sons. Richard’s strongest advocate is Henry Tudor himself.

Henry Tudor, who worked so hard to blacken the name of the man he had supplanted; Henry Tudor, who suppressed the Titulus Regius because he dared not remind the world of the validity of–Richard’s claim; Henry Tudor, who has by his own tortuous schemings, gradually revealed, provided the strongest proof of Richard’s innocence. If Richard was guilty, why no accusation in the Act of Attainder? Why no solemn requiem mass for the dead children at a time when these pious exercises were considered of such importance, and which would surely have been ordered by Henry from policy or by his Queen as a family duty to her brothers? Why did it take Henry twenty years and a faked posthumous confession to establish a story whose main outlines he must have discovered within twenty four hours of taking possession of the Tower had there been a word of truth in it? Why all those years of anxiety over pretenders to the throne if proof of their impostures lay ready to his hand? How is it possible that in all that time he could gain no clue to the mystery if the story which he ultimately gave out had been true? No word of the taking over of the Tower for one night by Tyrell, coinciding with the disappearance of the children, and no hint of the reburial by the priest who could not have carried out his task alone and in complete secrecy. If, on the other hand, the bodies were lying all the time under the staircase where they were originally supposed to have been buried, why did Henry not find them when he made ‘diligent search’? And why was Tyrell not tried on a charge of murder and regicide instead of being hastily executed on a minor charge before his ‘confession’ was made public? That Henry had to make use of such a ridiculous story to bring about a result which he had ardently desired for so long is the best possible proof that he was unable after years of trying to find any grounds at all for his accusation.

In English law a person is innocent until he is proved guilty – not merely asserted or supposed to be guilty on prejudiced evidence. In the matter of Richard III and the supposed death of his nephews there is no case to bring before the court at all. It should be dismissed from the bar of history.

Richard’s whole reign, short as it was, clearly shows that he intended to rule with justice and mercy. The liberal reforms which he sponsored in his one parliament arc an indication of what he might have done had he been given time. His treatment of both friend and foe was noticeable for its generosity. After Buckingham’s rebellion there were few executions and he showed great, and in the event, misplaced leniency towards Lady Stanley and innumerable lesser offenders.

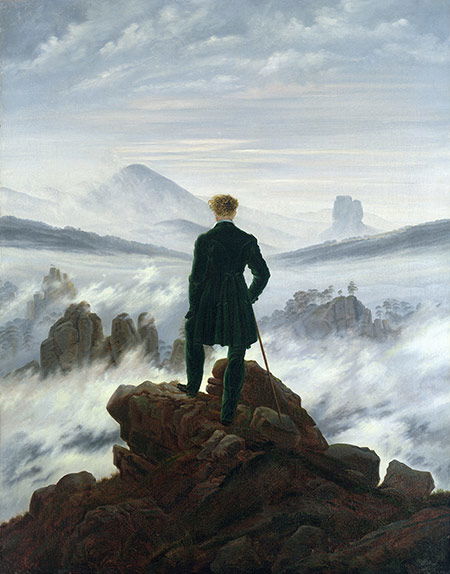

The reason for his failure and his downfall lay in the fact that he was no politician, and that he had no sense of expediency or of timing. His goal was what he held to be right and he aimed straight for it regardless of the enemies he might make on the way. Honesty and straightforwardness, the very qualities which had brought him success as a soldier and an administrator, were responsible for losing him the support of the powerful men of his kingdom, who found their own interests to be in direct conflict with their King’s determination to ‘use his authority and office as he ought’ (Buck, Vergil). Nevertheless, he might have weathered all storms had it not been for the devastating blow he sustained in the loss of his only son and heir, a blow which left him a broken man and the kingdom in the desperate hazard of an unsecured succession, and which together with Richard’s own fatal tendency to place his trust in traitors, gave to Henry Tudor, his scheming mother, and a handful of treacherous nobles their chance to take the road which led to the tragic disaster of Bosworth field.

The only stain on Richard’s memory remains the execution of his false friend Hastings. Of the many thousand words written about him, the fairest and most balanced summing up is that of Thomas Carte: Facts, and the general tenor of a man’s conduct best show his real character, and all the virulent and atrocious calumnies founded purely on surmises, a perverse imagination, or downright falsehood, and thrown upon Richard by the flatterers of his successor whose cruelty came by that means to be overlooked, will never efface the just praise due to Richard for his excellent laws and his constant application to see justice impartially distributed and good order established in all parts of England.

![The Betrayal of Richard III The Betrayal of Richard III]()

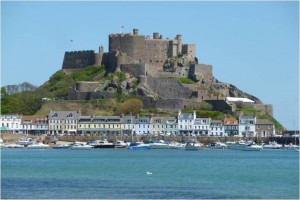

In this classic work, Peter Hammond and the late V.B. Lamb survey the life and times of Richard III and examine the contemporary evidence for the events of his reign, tracing the origins of the traditional version of his career as a murderous tyrant and its development since his death. The evident grief of the citizens of York on hearing of the death of Richard III — recording in the Council Minutes that he had been 'piteously slane and murdered to the Grete hevynesse of this citie' — is hardly consistent with the view of the archetypal wicked uncle who murdered his nephews, the Princes in the Tower, and there is an extraordinary discrepancy between this monster and the man as he is revealed by contemporary records.

An ideal introduction to one of the greatest mysteries of English history, this new edition of The Betrayal of Richard III is revised by Peter Hammond and includes an introduction and notes.

![Caudron [G 4s] Signalling - The great French aerial reconnaissance Pilot Capitaine Roeckel commented on the ability of aviation to support artillery targeting with, “The point of aim - whether it is a trench, a battery, or a shelter - his will for destruction concentrates upon that.” Caudron [G 4s] Signalling - The great French aerial reconnaissance Pilot Capitaine Roeckel commented on the ability of aviation to support artillery targeting with, “The point of aim - whether it is a trench, a battery, or a shelter - his will for destruction concentrates upon that.”](http://www.thehistorypress.co.uk/media/wysiwyg/Caudrons_Signalling.jpg)